Building forms with Uniform

Modeling Forms in Uniform

In Uniform, a “form” is not a special entity but simply a composition of components. Uniform allows you to define a Form component that acts as a container with one or more slots. Form fields like text inputs, dropdowns, and checkboxes are implemented as individual components that can be placed into the form’s slots. This is a composable, headless approach: content editors assemble forms by adding components to slots, rather than using a fixed form builder UI.

How it works: The Form component contains slots (e.g. a slot for form fields, another for form buttons). Each field (text, dropdown, etc.) is a Uniform component that will render an appropriate input element. When the form is rendered on the front-end, all these components work together: the form provides context and state management for the child field components, and includes the HTML <form> element to capture submission. This modular design means you can reuse field components and arrange forms flexibly in the Canvas editor.

If you are new to Uniform, it may help to review the basics of Uniform (specifically, components, and compositions) in Core Concepts and the Canvas composition guide. In brief, Uniform lets you define components in code and then use them in a visual editor to build pages (compositions). In this case, we’ll define a Form and field components in code so that they become available in the Canvas editor for use.

Setting Up the Form and Field Components

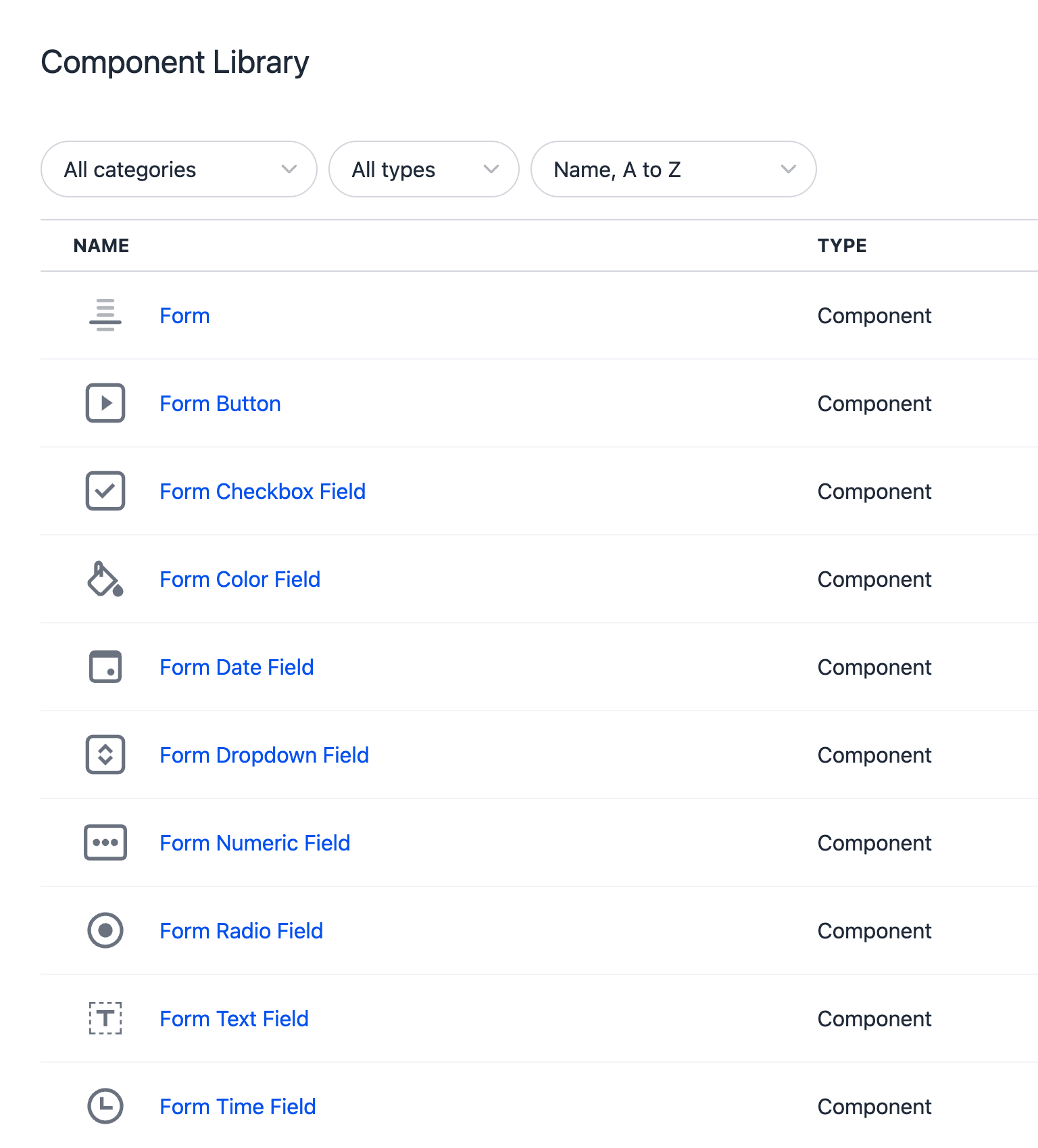

First, you need to implement the Form component and various form field components in your front-end project, and register them so Uniform knows about them. You will then need to create matching component definitions inside your component library in your Uniform project. For instance, a component of type "formTextField" will use the FormTextField React component.

In the example above, we have types for a form and a variety of form field types (text, numeric, dropdown, checkbox, radio, date, time, color) as well as a form button. You can choose which field types you need; a typical setup would include at least text fields, dropdowns, checkboxes, and a submit button.

Building the Form Component (Container with Slots)

The Form component serves as the container for the entire form. It will render a <form> element and use Uniform slots to define where child components (fields and buttons) go. It also provides a React context to manage form state (more on that shortly).

Key features of the Form component:

- Slots: It defines one slot (or possibly multiple) for form fields, and another slot for form actions/buttons. In our example, the slots are named

"formFields"and"formButtons". Any components added into these slots will be rendered in those locations. - Parameters: The Form might have parameters like a form title (to display as a heading) and a form identifier (used for submission logic). For example, a Form Name parameter can be used for a heading or form title, and a Form Identifier parameter serves as a unique ID for the form (helpful for backend processing or analytics).

- Submit handling: The Form component will handle the form submission event and trigger an API call (we'll cover this in a later section).

Below is a simplified excerpt of the Form component’s JSX structure showing how it renders a title and slots for fields and buttons:

In the code above, <UniformSlot name="formFields" /> will render all child components that were added to the Form Fields slot of the composition. Similarly, <UniformSlot name="formButtons" /> renders anything placed in the Form Buttons slot (typically one or more button components). The formName (a prop corresponding to a component parameter) is displayed as an <h2> heading at the top of the form in this example.

The onSubmit={handleSubmit} on the <form> element means the Form component intercepts the form submission. Usually, handleSubmit will collect the form data from state and send it to a backend API (we will detail this soon).

Form State Context: In the referenced repo, the Form component uses a React Context to manage form state. When the Form component renders, it wraps its children with a context provider (often called FormProvider) that holds all field values. This context allows each field component to register itself and update its value without needing individual state in each field. For example, on initial render the Form extracts all field components in the slot and initializes state entries for each (including default values for dropdowns, etc.), and provides a context with a centralized formData object and a handleInputChange function. This way, as users fill in the fields, each field component calls handleInputChange to update the shared formData. The Form can then easily collect all data on submit. (The context also makes it easy to reset the form or perform actions like setting a personalization quirk when the form is submitted — more on that in the submission section.)

Creating Field Components (Text, Dropdown, Checkbox, etc.)

Each form field is a separate React component that represents an input control. Common examples are Text Field, Dropdown Field, Checkbox Field, Radio Button Field, etc. In Uniform, these are implemented as components so that an editor can add whichever fields they need into the form’s slot.

Let’s walk through a Text Field component as an example, since it’s similar to other input fields:

In this code (from the FormTextField component), the field component renders a <label> and an <input> text box. Several important things to note:

- Parameters to Props: The Uniform's component parameters (e.g. Label, Placeholder, Required, Type, Name/Identifier) are received as props in the React component. In this example,

label,placeholder,requiredandtypeare props. Thenameprop here corresponds to an identifier for the field – it’s very important that each field has a unique name/identifier so it can be tracked. In the code, the field generates anidentifierconstant by sanitizing the provided name (e.g. lowercasing and replacing spaces) or generating a UUID if none is provided. Thisidentifieris used as the form field’s HTMLnameandidattributes, and as the key in the form state object. - Context and State: The component uses

useFormContext()(from the Form’s context provider) to get access toformDataandhandleInputChange. Thevalueof the input is controlled byformData[identifier]?.value, which comes from the shared form state. TheonChangehandler calls the context’shandleInputChange(identifier, newValue)to update the state when the user types. This makes the input a controlled component tied to the central form state. - Rendering: The actual HTML output is straightforward: a label associated with the input, and the input itself with the appropriate attributes. The

requiredprop, if true, adds therequiredattribute to enforce HTML5 validation, andtypecould be "text", "email", "password", etc., depending on what was set in your Uniform component. The codebase shared at the bottom of this article allows the editor to choose the input type for a text field, so you can use the same component for emails, numbers, etc. by changing the type.

Other field components follow a similar pattern:

- A Dropdown Field (

FormDropdownField) renders a<select>element. Its parameters include a list of options. In the Uniform forms library, each option has a label and a value, and can carry flags for “default”, “hidden”, or “disabled” states. The dropdown field component will initialize its state with the default option selected (if one is marked default) and render<option>elements for each provided option. When the user selects an option, it updates the context state with that value. - A Checkbox Field (

FormCheckboxField) renders an<input type="checkbox">. It stores the checked state as a string"true"or"false"in the form data (the example implementation converts the booleane.target.checkedto a string before callinghandleInputChange). You might just have a label and default value for a checkbox field, given that the value is inherently the checked state. - A Radio Group Field (

FormRadioField) can be implemented similarly to dropdown, with options; the referenced example project uses an options list and tracks a selected value much like the dropdown (with an initial default selection if specified). - You might also add more components for date/time pickers, color pickers, etc. as needed – the concept remains the same.

When defining these components in Uniform:

- Name/Identifier: Ensure each field component has a parameter for an identifier or name (for example, “Field Name”) that the content editor will set. This value is used to identify the field’s data. In practice, if an editor leaves it blank, the code should generate a unique one (as we saw, a UUID) to avoid collisions, but it’s best for editors to provide a meaningful name (like

"email","phone", etc.). The identifier will appear as the JSON key in the form submission payload. - Label: A human-friendly label for the field (e.g., “Email Address”) which is shown on the form.

- Placeholder: (if applicable) Placeholder text for inputs.

- Required: A boolean to indicate required fields. The React component can add a

requiredattribute (and you can also enforce this server-side on submission). - Options: For dropdowns or radio groups, a list of options. In Uniform, this might be implemented as a nested component list or a Block parameter. In the starter kit, the Dropdown Field has an

optionsBlock parameter which is a list of Option objects, each with sub-fields for label, value, and anoptionsarray of flags (to mark default/hidden/disabled).

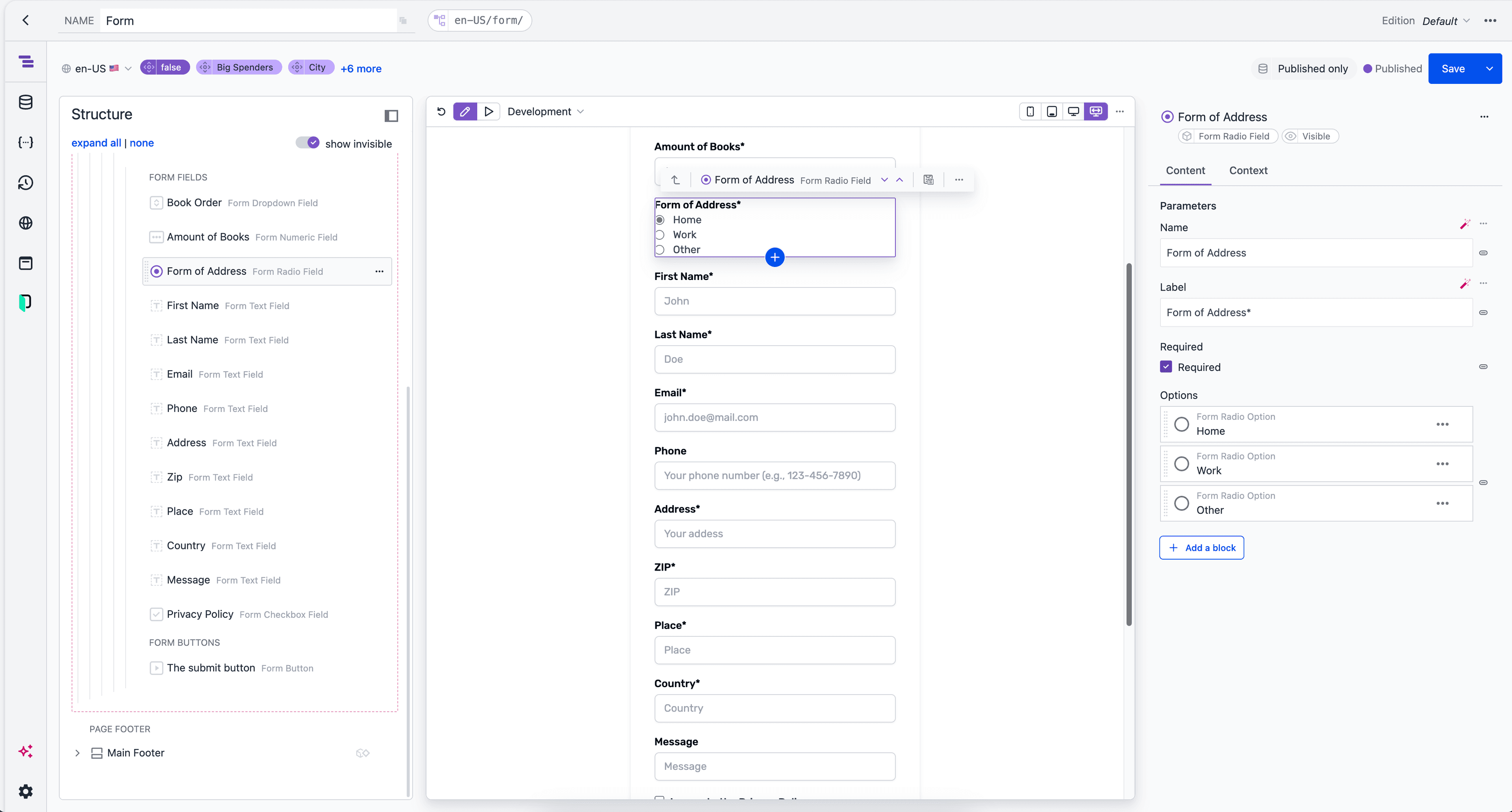

Using the Form and Fields in the Canvas Editor

Once the Form and its field components are set up in code and registered, content authors (or you, as a developer in the Canvas editor) can build forms visually:

- Add the Form component: In Uniform Canvas, create a new composition (or open an existing one) where you want the form. Add the Form component onto the canvas (for example, as a component within a page section). If the Form component has parameters like Form Name or Form Identifier, set those in the Canvas properties panel. For instance, give it a Form Name like "Contact Us" to use as the form title, and an identifier like "contact-form" (this could be used by the backend or for analytics).

- Add fields to the form: You will see the Form component has slots (often visually indicated in the Canvas editor). For our setup, there would be a formFields slot and a formButtons slot. Start adding field components into the formFields slot. For example, add a Form Text Field component for a “Name” field:

- Set its Label to "Your Name".

- Set its Placeholder to "Enter your name".

- Set Required to true if you want to enforce that it’s filled.

- Set the Field Name (identifier) to something like

"name". Repeat this for each field you need (Email, Message, etc.), using the appropriate component types (e.g. a Form Dropdown Field for a dropdown list, Form Checkbox Field for a checkbox, etc.), and configure each field’s parameters.

- Add the submit button: Finally, add a Form Button component into the formButtons slot (this could be called Form Submit Button in the Canvas UI depending on how it’s defined). Set its label text to something like "Submit". In our implementation, the FormButton component also had a

typeprop (which could be "submit", "reset", or "button"). You should choose"submit"so that it will submit the form when clicked. - Save and Preview: With the form assembled, you can preview the composition. You should see your form rendering with all the fields and the submit button. Because of the controlled inputs, as you type into the fields, the state updates. If a field was marked required, the browser will enforce that on submit.

From a content editing perspective, this is very similar to using a traditional form builder: the editor drags and drops fields, configures their labels and settings, and places a submit button. The difference is that under the hood it’s leveraging your React components and Uniform’s composition model, which means you have full control to customize how fields work in code, as well as how submissions are going to be processed.

Handling Form Submission on the Front-end

When the user fills out the form and clicks Submit, our Form component’s handleSubmit function is invoked. In the example project, this function prevents the default browser submission and instead sends the data to a custom API endpoint via fetch. Let’s examine how the form data is sent to the server:

A few things to note here:

- It posts to the endpoint

/api/forms/submit. We will need to create an endpoint like this on our backend (in a Next.js app, this would be a file likepages/api/forms/submit.tsor in theapp/apiroute directory). - The content type is JSON. The form data in the included example project is serialized with

JSON.stringify. The object being sent includes a propertyformIdentifier(which was a parameter on the Form component, identifying which form is being submitted) and then spreads...formData.formDatais the state object containing all field values. The structure of this object, as produced by the Uniform form context, maps each field’s identifier to an object with that field’s currentvalue(and possibly an index or metadata). For example, the payload might look like:

- Each field identifier (like

"name","email","subscribe") has an object. In this implementation the value is nested undervalue. Depending on how you design your form context, you might also choose to send a simplified payload where each field maps to the value directly, but the referenced example project parses this nested structure on the server. - After sending the request, the code handles the response. If

response.ok(HTTP 200), it proceeds to do any success actions. You may add a concept likeformActions– for example, one action could set a Uniform quirk in the personalization context – and once they have been executed you reset the form state (clearing the fields).

Personalization note: Uniform’s context can store personalization flags (“quirks”). The example project supports an action type (in formActions) called “set quirk” which can update the context if the form is successfully submitted. For example, a form could set a quirk like newsletterSubscribed = true upon submission, which you could use to personalize content later. Configuring such actions would be done in the Canvas editor. This is an advanced feature, but it’s good to be aware that forms in Uniform can tie into the broader DXP capabilities like tracking user preferences.

Implementing the Backend Form Submit Endpoint

On the server side, we create an API route to receive the form POST. In a Next.js project, this is typically done by adding a file under pages/api if using the Next.js page router. If you are using Next.js App Router or other frameworks, this implementation will be different. We’ll assume a file path pages/api/forms/submit.ts for this example.

This endpoint should:

- Accept only POST requests (respond with an error for others if needed).

- Parse the JSON body of the request.

- Perform any necessary validation or spam checks.

- Process the form data (e.g., save it to a database, send an email, or integrate with an external service).

- Return a JSON response indicating success or failure.

Here is a simple example implementation of /api/forms/submit in Next.js (TypeScript):

Let’s break down what this example is doing:

- It ensures the method is POST, otherwise returns 405 Method Not Allowed.

- It reads

req.bodywhich, thanks to Next.js, will already be parsed as JSON (since the front-end setContent-Type: application/json). Thedataobject structure will contain whatever was sent. As noted, each field will be indatawith its identifier as the key. In our example payload structure,data.name.valuewould be the actual value of the Name field. - Spam protection: We included a check for a field named

"honeypot". If you plan to use a honeypot, you can add a hidden field in the form (e.g., a text field that is visually hidden via CSS) and name it “honeypot” (or any name you choose). Bots often fill every field, but real users won’t see it. Ifdata.honeypot.valueis non-empty, we treat it as spam and return a success (HTTP 200) without actually doing anything (to the bot it looks like a successful submission, but we ignore it). This prevents spam submissions from being processed. - Validation: The example checks that required fields (

nameandemail) are present and not empty. Since the values are indataas strings, we trim and verify they're not blank. We respond with HTTP 400 and an error message if validation fails. The front-end will receive this and show an alert with the message (because the form component expects a JSON{ message: "..." }on error). You should mirror any "Required" logic that exists on the front-end in the backend as well, to avoid situations where a malicious user bypasses front-end checks. - Processing data: In a real application, this is where you do something useful with the submission. Common actions include:

In the code above, we’re just logging the submission. You would replace that with actual processing logic. Note thatdata.formIdentifiercan be used to distinguish which form was submitted if you have multiple forms using the same endpoint. For instance, you might handle a "newsletter-signup" form differently from a "contact-us" form based on this identifier.- Email notification: You might use a service or SMTP to email the form contents to a recipient (e.g., a contact form email).

- Database or CRM save: You could save the submission to a database, or forward it to a CRM/marketing automation system via API.

- Triggering Uniform personalization: In our example, Uniform’s front-end already handles setting any personalization quirks. The backend typically just needs to record or relay the data.

- Response: If everything goes well, we return a 200 with a success message. If an exception is thrown during processing (e.g., an error from an external service), we catch it and return a 500 with an error message.

This simple endpoint is designed to handle dynamic sets of fields. We didn’t hard-code any field names besides the honeypot and required checks. We treated data as an object that could contain any fields. In a more generalized approach, you might iterate over data keys (excluding formIdentifier) to process them generically (for example, constructing an email message that lists all field labels and values). Because Uniform forms are defined in Canvas, the set of fields can change without code changes – your backend handler should be flexible with regard to field names.

Wrapping Up

We’ve covered how to build forms in Uniform by creating a Form component with one or more slots, and field components for each input type. You learned how to assemble these components into a working form using Uniform, and how to handle submission logic on the backend using a custom API endpoint.

With this approach:

- Developers retain full control over form markup, state management, and submission behavior.

- Content editors can visually assemble forms in the Canvas editor without developer support.

Key takeaways:

- Treat forms as compositions of components: the form is a container, and fields are modular components.

- Each field component manages its own portion of state via a shared form context, making dynamic forms possible.

- Register all components with Uniform so they can be used in the visual editor.

- Design the backend endpoint to handle JSON submissions and to be robust against varying field sets, spam, and validation issues.

- You can extend this basic setup with more field types or custom behaviors (file uploads, multi-step forms, CAPTCHAs, etc.) as needed, by following the same pattern of component creation and state management.

See it in action

Give our live example a go.

For further reading or reference code, you can check out our Component Starter Kit Forms example on GitHub which provided the basis for the code shown here. It contains the full source for the Form and field components discussed in this article.